As an Irishman, Oscar Wilde was in some respects an exotic outsider in 19th century Oxford.

“You ought to hear him talk!” his English friends told the students who had not yet met him. One of Wilde’s Magdalen College chums, William Ward, fondly remembered his allure. “There was something foreign to us, and inconsequential, in his modes of thought,” Ward said. “We, his intimate friends, did not judge him by the ordinary standards.” For all his prominence as an Irishman in Oxford, Wilde conformed outwardly to the manners of the English gentlemen around him by adopting their diction. Despite his friends’ fascination with his Irish brogue, it progressively disappeared. “I wish I had a good Irish accent,” he said in later life, regretting the loss and explaining that “my Irish accent was one of the many things I forgot at Oxford”.

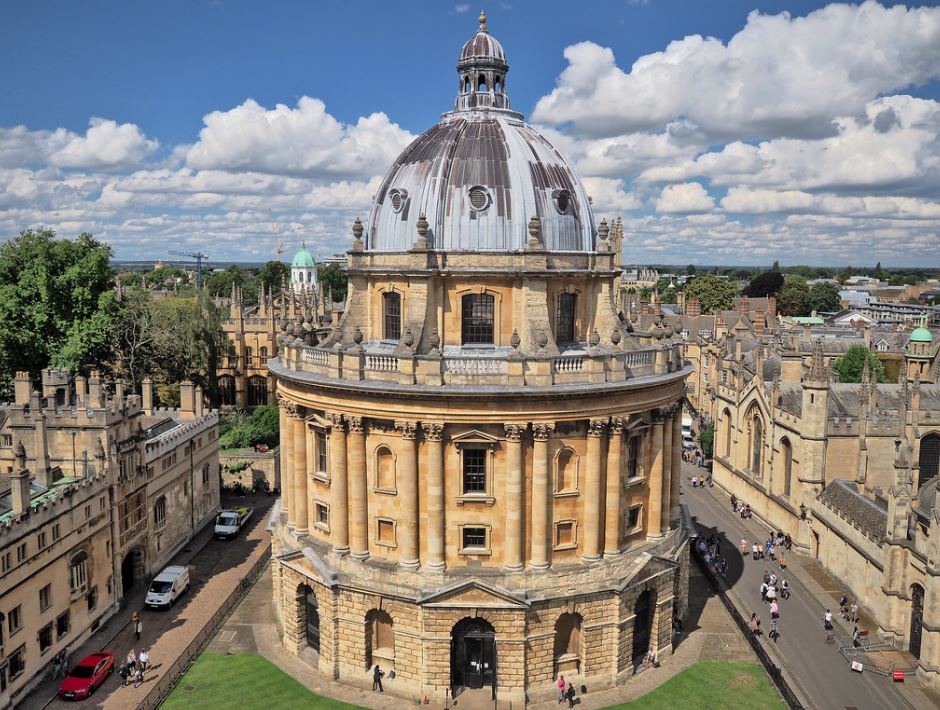

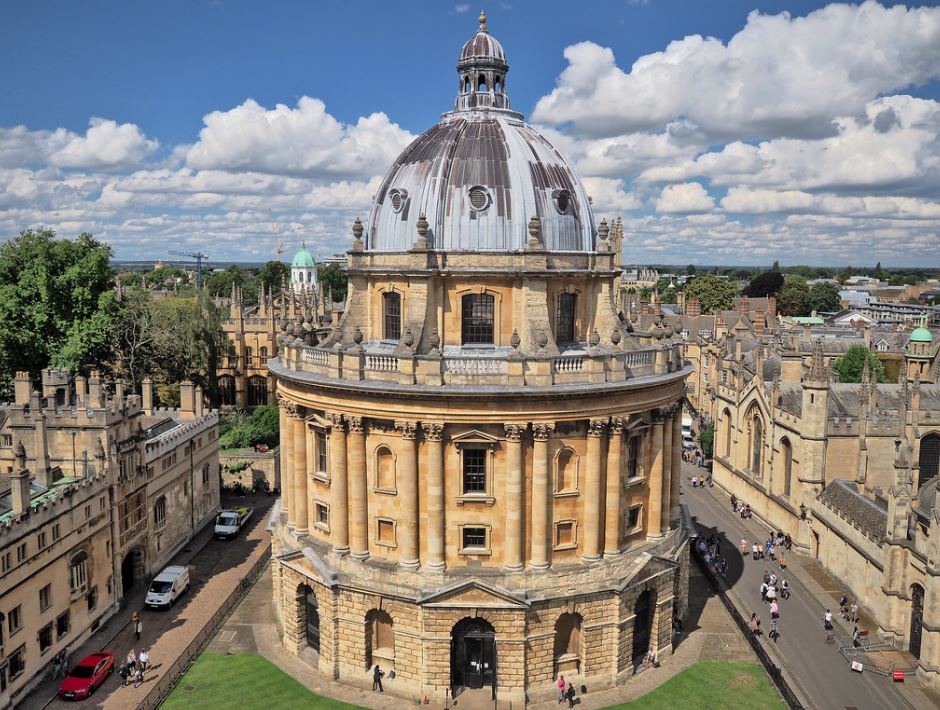

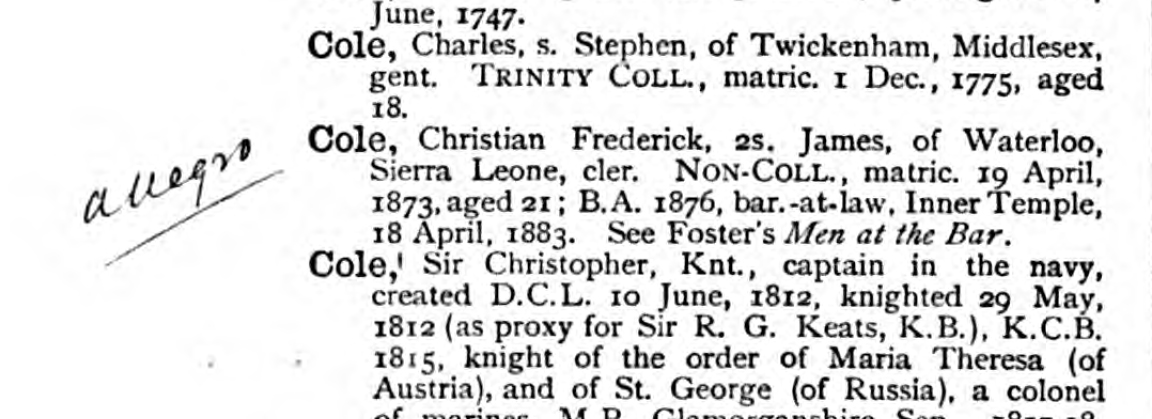

Wilde was special, but there were other Irishmen at Oxford. Christian Cole’s ethnic difference was much more marked, as his entry in the register of University members shows. Cole was almost unique: a statistical aberrance in the University’s six-hundred-year history.

Christian Cole’s entry in the copy of Foster’s Alumni Oxoniensis 1715-1888(Oxford: 1887-1888), v.1. p. 274. Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford: Bodleian Libraries: Special Collections R.Ref.135.

The few statistics we have about Black Victorians paint a striking picture of how rare a Sierra Leonean like Christian Cole was. In England and Wales in 1871 only one person in 225 was foreign-born. That’s roughly 0.44% of the population. People from Africa and Egypt counted for less than 0.24% of the foreigners in Britain. Of these “foreign-born” few were Black. Most were ethnically European. They were not visual minorities.

A decade later, the figures had hardly budged. By 1881, the total population in England and Wales was nearly 26 million, of which only 258 people were born in Africa, like Cole. Of those 258 people, 196 lived in London. The remaining 62 African-born people were sprinkled throughout the rest of England and Wales. Imagine how unlikely it would be to encounter one of them. And remember, most of these men and women were not visual minorities. So how much first-hand experience did the average white Victorian have of Black Africans? Probably not much, especially outside of London, Liverpool and seaports like Bristol, Portsmouth, and Plymouth. Cole was more than a visible minority. He was a statistical blip, an outlier.

In the video below, Judge Karen Stevenson, the first African-American woman to win a Rhodes Scholarship, discusses her experiences of being part of the first cohort of women at Magdalen in 1979:

In the video below, 2018 Rhodes Scholar Camille Borders, MPhil student at Magdalen, reflects on the experiences of Cole, Locke and Judge Karen Stevenson:

By the time Alain Locke turned up in Oxford, in 1907, there were a few more students of colour at the University, although as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke remained unique. Even before his arrival in Oxford, his intellect was highly praised. Dr Robert Ellis Thompson wrote the following in a letter recommending Locke for admission to Harvard:

I presume you know he is a coloured youth…his white classmates accepted him on perfectly equal terms…he is by much the ablest student in the graduating class of the School of Pedagogy of this year.”

Dressed with panache and discreetly homosexual, Locke modelled himself on Wilde by imagining Oxford as the place to make himself over. Like Wilde, Locke hoped to become a slightly different person there, a person he described to his mother as “really cosmopolitan.” That new person, he told her, was going to escape the prejudice Alain Locke had experienced in the United States. “I’m not going to England as a Negro,” he informed her, “I will leave the color question in New York.” Oblivious to Locke’s hopes and plans, the colour question had designs of its own. It followed him across the Atlantic just as Wilde’s brogue came across the Irish Sea to Oxford.

In his first term of study, Locke learned that his wishes were not going to be fulfilled in England. By the early decades of the twentieth century, attitudes had barely changed since the days of Christian Cole. The implicit principle, it seemed, was not to exclude people of colour, but simply not to include them.

The University was “a land of class distinctions,” Locke observed in an essay he wrote during his first year at Oxford. He proved himself a gifted reader of its social exclusions. Locke quickly discovered that British racism worked covertly, not as it did in the United States where Jim Crow laws overtly mandated racial segregation. British exclusion was more discreet but it was still effective.

For Oxford alumnus and Rhodes Scholar Donald “Field” Brown, Locke’s legacy is important:

During my time at Oxford, Locke inspired me to embrace change in ways that radically tested my fundamental assumptions about people. Because I did, I was able to grow in ways I never expected to while there. He stands as a model for what Oxford can do for hungry students open to embrace what the university has to offer them.”

In 2019 as part of this exhibition’s events, Mansfield College B.A. English students Serena Arthur and Oluchi Ezeh chaired a public discussion about Alain Locke’s legacy. Here is what they said:

Was there a bridge from his past to our present? Yes. We, too, had experienced the “slow but persistent change” of ideas in Oxford. We, too, had to contend with a glorious but intimidating institution we weren’t quite sure we fit into. We had walked the same hallowed academic spaces, spoken with the same reverence for them and, in the same breath, had the same anxieties Locke had. And we, too, felt compelled to write about it. Locke was the “midwife” to young black aspiring writers. This metaphor of birthing a movement rang true to our own experiences. Our increased “race curiosity” led to support for Onyx, a magazine edited by Oxford students of African and Caribbean heritage, including us! We wanted to celebrate and inspire black student writers. Just as Locke felt he needed to voice his experience, so have we, and so will many others after us.

Founded in 2017 by Theophina Gabriel (Regent’s Park College) and Birmingham Young Poet Laureate Serena Arthur (Mansfield College), Onyx magazine was published by 8 dedicated Black Oxford women students who raised over £4,000 and published the first 88 page issue. The publication defines itself as “a space where we would be free to be creative in our expression without necessarily having to mention ‘the struggle’”.